Having completed the Royal Navy’s last great journey of exploration

under sail power, HMS Terror’s next commission was destined to be the first

major voyage of discovery to use auxiliary screw propulsion.

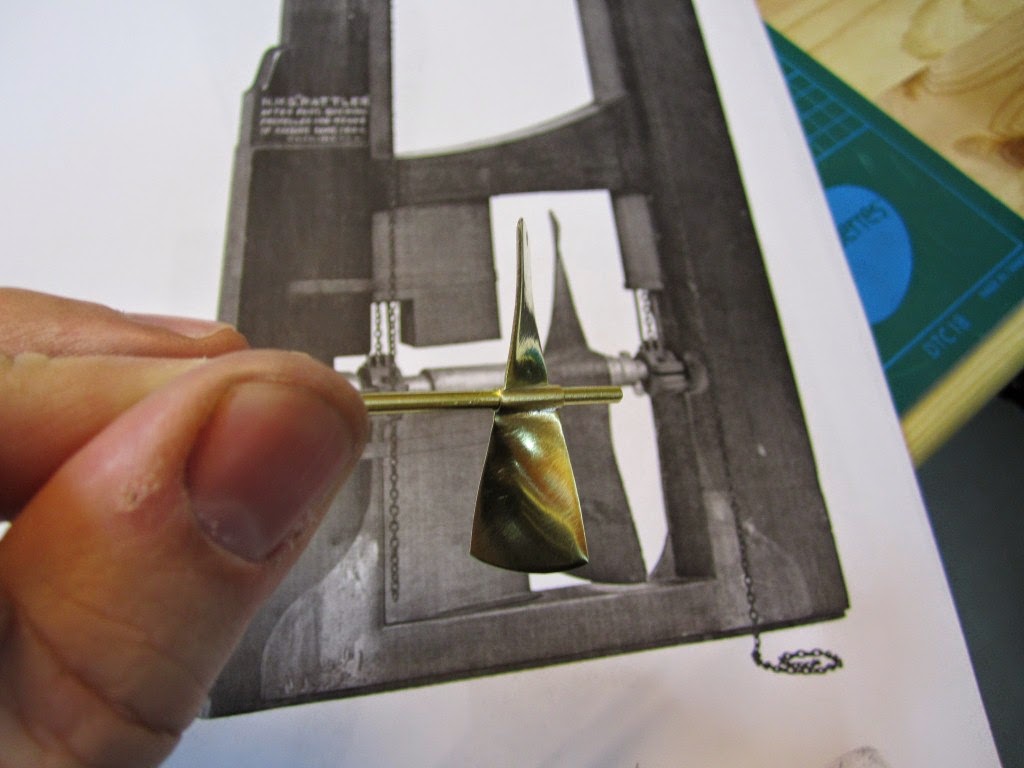

The 1845 stern plans show that Oliver Lang chose a two-bladed Smith

type propeller for the voyage (Battersby and Carney 2011:204). This choice

makes perfect sense; in January of 1845 the Admiralty had just concluded

extensive tests of screw propellers on HMS Rattler, finally settling on a

two-bladed design by Smith (Carlton 2012:6; see also Bourne 1855:136).The propeller was likely made of

gunmetal, similar to those used in subsequent Franklin search vessels (Dickens

1850:8) and other Royal Navy ships of the era. According to Lang’s plans, the screw

was ca. 6 feet 11 inches in diameter (from tip to tip). HMS Erebus and Terror also

carried a spare four-bladed propeller of the Woodcroft type (Battersby and

Carney 2011:204). Roughly the same diameter as the Smith propeller, its shape and

size would have necessitated that it be unshipped over the side of the vessel

rather than through the propeller well.

|

Plans for HMS Terror's propeller. The filling chocks used when the

propeller was unshipped are on the right. |

Following others (Battersby and Carney

2011:204), I originally believed that the propeller was set

in a frame that would sit flush inside the fore and aft rails/grooves in

the propeller well (the rail system will be described in my next post). This

was a prudent assumption, as a frame-mounted propeller was standard in screw-assisted

vessels of the Royal Navy in the latter half of the 19th century.

The frame was an important feature because it was used to raise and lower the

propeller along the rails in the well, while providing stability when it was

in use.

However, despite their common use in the

era, I was puzzled by the fact that no frame is visible in the 1845 stern plan.

I recently purchased high resolution scans of the plan, which permitted me to

read Lang’s thorough annotations. Needless

to say, the last annotation in the list, labeled “P”, describes the reason that

Lang didn’t include a frame in the plan:

“P: Propeller in place with a hole in the

end of the fan to take it up by and to lower it down in place when required.“

The annotation exposes the highly expedient

and experimental nature of the design, which represented a great simplification

of the complex propeller lifting system used for the Rattler (view it here).

While very rare, the hole-in-blade lifting system was subsequently employed on RRS Discovery by Robert Falcon Scott during his 1901 Antarctic Expedition (pictures

of the hole in the blade can be found here

and here).

In fact, RRS Discovery appears to have borrowed many design elements from

the Erebus and Terror, a testament to the advanced and efficient nature of

their systems.

Because Lang’s plans don’t show precisely

how the propeller articulated with the rails in the well (the rails on the plan

obscure those details), I was forced to speculate that the propeller included

two retaining ferrules which would both seat the propeller and guide it as it

was raised and lowered into position along the rails. In modeling this, I took

inspiration from the ferrules used in contemporary

Admiralty models and the RSS

Discovery, though I admit they are highly generalized and speculative.

References:

Battersby, William, and Carney, Peter

2011 Equipping HM Ships Erebus

and Terror, 1845. International Journal

for the History of Engineering &

Technology 81(2):192-211.

Bourne, John

1855 A Treatise on the Screw Propeller with

Various Suggestions for Improvement. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans,

London.

Carlton, John

2012 Marine Propellers and Propulsion. Butterworth-Heinemann,

Oxford.

Dickens, Charles