Today marks the 201st

anniversary of the launch of HMS Terror in Topsham, Devon. It also marks the first anniversary of Building Terror. I envision the blog as a

place to document the history and architecture of one of the world’s greatest polar

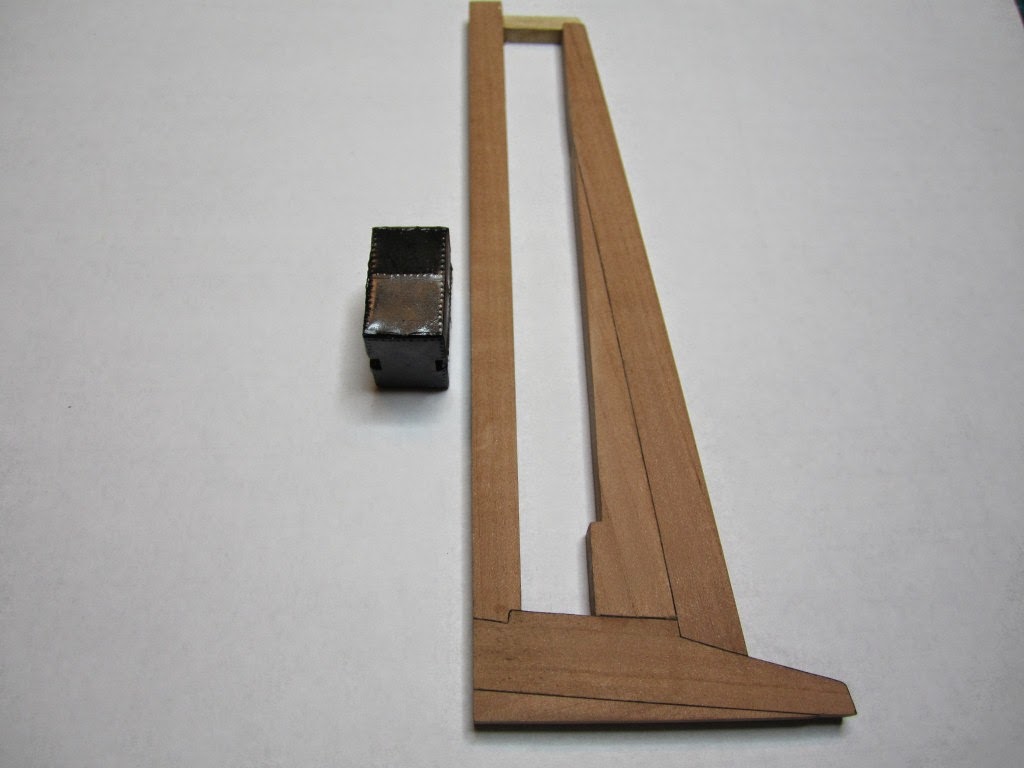

exploration ships. I’m telling that story through my project to

build the world’s first accurate model of the Terror as she appeared in 1845.

I’ve been very pleased with the public response

to the blog, which has received nearly 10,000 views in the last year. It has led

me to correspond with some of the foremost scholars of both the Franklin

Expedition and historic sailing vessels of the 18th and 19th

centuries.

I research each part of the vessel in detail

as I build, so construction of the model has proceeded slowly, but on pace. I have duplicated much of the blog in a topic on Model Ship World forums, and the comments of the modelers, who are some

of the world’s most knowledgeable ship historians, will likely be of interest

to followers of this blog.

Building Terror has been accessed all over

the world, and my images and plans have popped up in numerous places, most notably

on the exhibit website for “HMS

Terror: A Topsham Boat”, hosted at the Topsham Museum

(Devon Museums).

I’ve had many requests for plans, images, and

even the model itself; others have asked me to write research papers or a

book on the architecture of the ship. For now my goal is simply to finish my plans

and model. When they are complete and accurate, I’ll decide what to do

next. If you have any ideas, I’d be

happy to hear them.

The many hundreds of hours I’ve spent

pouring over plans and researching this fascinating ship have been some of the most

rewarding I can recall. The Terror really was something else altogether– in her time, she was the pinnacle

of nautical science; the embodiment of the desire to explore,

document, and dominate the natural world; and the emblem of an empire’s dominion. Alone in the ice, she was the incarnation of the simple determination and

courage of men.

Even if she had never been part of the

Franklin voyage she would still have a place among the greatest exploration

vessels of all time. Yet Terror’s final two years sheltering her crew from the crushing

pack off King William Island proved her true mettle; there was nothing further

a polar exploration vessel could have achieved.

Some may say she didn't deserve

her fate. Her captain and crew certainly did not. But had she survived, she

would likely have been turned into a transport or scow and then broken up like HMS

Resolute. In whatever state she’s in, HMS Terror is still preserved somewhere

under the Arctic Ocean. The mystery of where she rests continues to draw us to

her. She deserves the attention.

.JPG)