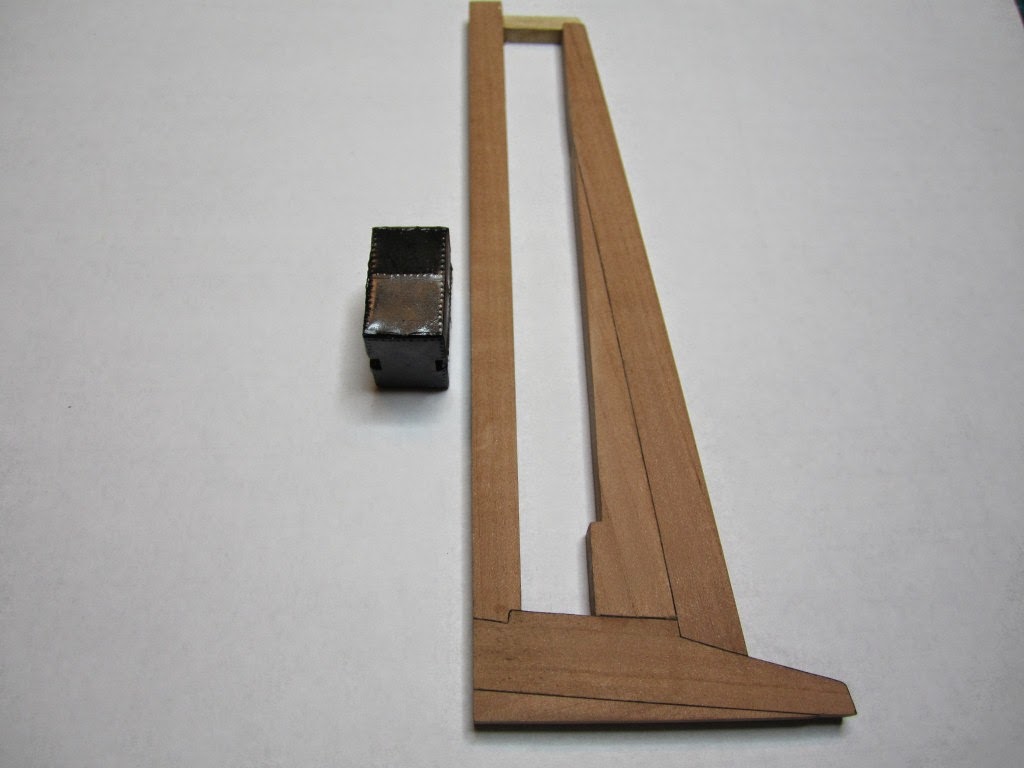

Size:

Hecla class bomb vessels were a slightly larger version of Peake’s earlier Vesuvius class design, the most notable difference being a fuller, more bluff, bow. In fact, the roots of the Hecla class can be seen in penciled-in annotations on the 1812 plans for HMS Vesuvius. The rationale behind the change appears to have been to address the poor sailing qualities of the Vesuvius class and the subsequent need to store more ballast to improve stability (Ware 1994:67). The inability of the Vesuvius class to carry sail in weather would plague the Terror throughout its career (see below).

The table below provides measurements of the general dimensions of the vessels and how these changed over time. Each of the measurements were taken directly from the plans, which I corrected for distortion and precisely scaled to the ¼ inch (1:48) Admiralty standard (to the extent possible given draughtsman’s errors). In the case of the Erebus, I did not have access to the original 1826 draughts, so I have cited dimensions reported in other sources (e.g. Ware 1994). Two of the measurements (moulded breadth and length of the gun [lower] deck) conform to standard nautical measurements, while the remainder are provided to demonstrate the overall size differences between the vessels.

It is important to recall that the sterns of both vessels were each modified twice; first in 1836/1839 to accommodate new rudder configurations, and again in 1845 to permit the fitting of the new screw propeller system. We have precise data on how the 1845 modifications affected the length of Terror, but not of Erebus. Here I have estimated the length of the Erebus in 1845 by applying the same change in length calculated for HMS Terror. How accurate this estimate might be is unknown, but it should be generally applicable.

Basic size comparison of the Terror and Erebus (* denotes an estimated value).

The table shows that, overall, the size differences between the ships were

very small, a matter of inches in many cases.

As I have discussed previously, I believe that the ships underwent a process of standardization in 1839, following Parry’s scheme of outfitting exploration fleets with identical equipment. We have good primary evidence for this written directly on the 1839 plans, which are labelled “HMS Terror and Erebus,...as fitted”. However, these plans are known to be based on the dimensions of HMS Erebus, and therefore questions have endured about how accurately the plans depict the fittings on HMS Terror. Below, I outline evidence that the Terror was outfitted almost precisely as depicted in the 1839 plans.

Deck Structures, Fittings, and Their Positions:

As outlined above, the titles of the 1839 plans indicate that both vessels were outfitted in the same manner, meaning that the deck fittings, hardware, and their positions should have been practically identical. However, the 1836 Terror plans show that important structures like hatchways and ladderways were located in radically different positions in 1836. Moving these would have required an extensive refit, and this raises valid doubts that important structural components were not moved on Terror. If they were not moved, logic dictates that their design was not changed as well. Perhaps other minor fittings were not modified either.

However, there is good primary evidence indicating that many of Terror's deck structures were moved and/or rebuilt to the 1839 standard. Though very faint today (and almost entirely invisible on the printed plans from the NMM), the 1836 Terror plans are heavily annotated with pencil markings. Colour and contrast correcting of the digital copies of the plans makes these markings easily visible, and shows many instances where structures were crossed out and moved. For example, the fore hatch on the 1836 plans was scratched out and moved to a more forward position, its size and position matching the 1839 plans precisely. Corresponding changes are shown below decks as well, indicating that lower deck hatches were moved to positions shown on the 1839 plans. Above decks, the companionway structure aft of the main mast was similarly scratched out, indicating that a new structure was built. The same occurred on the aft deckhouse(s), which appear to have been changed to a taller version.

Additionally, the paired midships pumps were crossed out on the 1836 HMS Terror plans, suggesting these too were changed to the Massies’ Patent pumps shown on the 1839 plans, a fact confirmed by contemporary newspaper articles (Anonymous 1839:405). There are no such markings on the capstan, windlass, or galley stove on the 1836 Terror plans, nor was the failed hot-water furnace struck from the plans. However, we know that the furnace was upgraded in 1839 because there is a report of it catching on fire (Davis 1901:20). Given this evidence, I think it is prudent to assume that other critical pieces of equipment were also upgraded with the Erebus in 1839.

Having outlined these similarities, it is important to note that because of its slightly smaller size, the position of deck fittings on Terror did differ somewhat from the Erebus. The following image illustrates some of these positional differences.

.jpg) |

| Example of the subtle difference in position of the skylights and mizzenmast on the two ships, measured from the position of the stem rabbet. The red indicates Erebus, the green is Terror. |

Bowsprit:

Reports from the Antarctic expedition (Ross 1847a; 1847b) indicate that Terror could not carry as much sail as Erebus and was constantly falling behind. Davis, Second Master on HMS Terror during the Antarctic expedition, indicates that part of the problem was that Terror’s bowsprit was too low (Davis 1901:17). Green-ink annotations on the 1836 Terror plans show that Oliver Lang fixed this problem in 1845 by raising Terror’s bowsprit by approximately 4.5 feet. This required that the bowsprit partners be moved nearly six feet aft, almost to the position of the foremast. The Erebus, with its higher draught and bowsprit, did not require this modification. The position of the bowsprit partners may have been the most drastic difference on the deck of the ships.

.jpg) |

| Plan highlighting the difference in position of the foremast and bowsprit partners. The red indicates Erebus, the green is Terror. |

Anchors:

The 1839 plans provide a list of the ten anchors required for each vessel. The largest anchors were identical in size, but the list shows that the kedges and smaller anchors differed, with the Terror’s being slightly smaller on all accounts.

Hull Fittings:

The 1836 plans for HMS Terror, as well as contemporary images from the Back voyage, seemingly indicate some external differences in the vessels. Specifically, in 1836 the solid ice channels and bulwarks on the Terror had gaps that did not exist on the Erebus. However, contemporary images of the Terror from both the Ross and Franklin voyages by Davis and Stanley, respectively, indicate that these gaps were closed on the Terror as per the 1839 plans.

There have been similar questions about the use of iron reinforcements on the catheads on the Terror as the 1836 plans show a wooden crutch instead of the iron version shown on the 1839 plans. Again, it is reasonable to propose that such a seemingly minor fitting may not have been changed in 1839. However, we know that at least one of Terror’s catheads was destroyed in 1842 (Davis 1901: 27), and it seems likely that "modern" iron reinforcements would have been used when the cathead was repaired, as these structures were obviously vulnerable.

Internal Strengthening:

The 1839 cross section plan shows a system of iron knees common on Royal Navy vessels of the period. In fact, the system is precisely the same as that introduced in the early 19th century by Sir Robert Seppings (a design for which he was awarded the Copley Medal from the Royal Society). However, debate persists that Terror did not have iron knees, because the 1836 plans include a cross-section that does not show them. This must have been an error of the draughtsman, because the 1836 cross section (and profile) shows the precise shelf and clamp system Seppings devised for use exclusively with iron knees. In short, there would be no reason to implement this system of shelf-pieces and clamps without iron knees (for reference, consult Goodwin 1987:80).

However, one specific difference in internal strengthening is shown in the 1839 cross section plans. It appears that two massive wooden riders which extended from the hold to the orlop deck were installed in HMS Terror in 1839. The reason for these riders is not recorded, but accounts by Davis written in 1842 (1901:19) indicate that the Terror had been severely weakened from the trauma of the Back voyage and such reinforcement might have been prudent on the aging and long-suffering Terror.

In Sum:

As quoted above, a newspaper report of the Ross Antarctic expedition stated that the Franklin vessels were "twin ships alike in build, in colours, in masts, and rigging, and, indeed, in every external appearance. An inexperienced eye could not tell the one from the other” (Anonymous 1839:405). Given the data presented above, I believe this to be a very accurate statement. The ships were originally designed and built, and then refitted, to be essentially identical - with just several inches separating them in most dimensions. Hopefully, the discovery of HMS Terror by Parks Canada in coming years will shed further light on contrasts between the ships.

References:

Anonymous

1839 The Antarctic Expedition. Gentleman’s Magazine 12:405-407.

Davis, J.E.

1901 A Letter From the Antarctic. William Clowes & Sons, London.

Ross, Sir James Clark

1847a A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, During the Years 1839-1843: Volume I. John Murray, London.

1847b A Voyage of Discovery and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, During the Years 1839-1843: Volume II. John Murray, London.

Ware, Chris.

1991 The Bomb Vessel: Shore Bombardment Ships of the Age of Sail. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis.

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2B(2).jpg)

%2B(Small).jpg)

%2B(2).jpg)

%2B(Small).jpg)

%2B(Small).jpg)

.JPG)