Oliver Lang's 1845 stern plans currently held in the National Maritime Museum's

collections. The title indicates that the plans are of HMS Erebus, but the dimensions

of the plan, especially the height of the bulwarks, match HMS Terror plans

more precisely. Additionally, the transcribed version of these plans occur on the

1836/37 profile plans for HMS Terror, and match the 1812 plans for Terror

relatively accurately.

In February 1845, Oliver Lang, Master Shipwright at Woolwich,

faced a daunting challenge. The Admiralty, under pressure from Parry, had

decided to outfit HMS Erebus and Terror for auxiliary screw propulsion, powered

by small passenger locomotives.

Screw propulsion was in its infancy and contemporary

designs, based on patents filed by Francis Pettit Smith and others, called for

the placement of the propeller opening in the deadwood of a steam powered vessel

(Bourne 1855:28). However, applying such a modification to polar vessels would

critically weaken the stern, and Lang knew from the Terror’s first arctic

expedition that even the most robust sternpost was severely vulnerable when

overwintering in sea ice. How could he protect the ship’s stern from the pack

when a gaping hole had to be cut in the deadwood for the propeller?

His solution appears in a plan dated March 17th, 1845, which

was subsequently transcribed onto the 1836/37 profile plan for HMS Terror.

Instead of altering the ship’s existing stern, Lang simply extended the stern

of the ship aft by adding a new keel section, onto which a new rudderpost and

aperture for the propeller were attached. The 1836/37 plans seem to show that Terror’s

original sternpost had been modified for Back’s voyage, but the 1845 annotations clearly indicate that

Lang reconstructed it to the same configuration used in Terror’s original

design (alternately, it is possible that Terror’s stern was not modified in

1836 as planned).

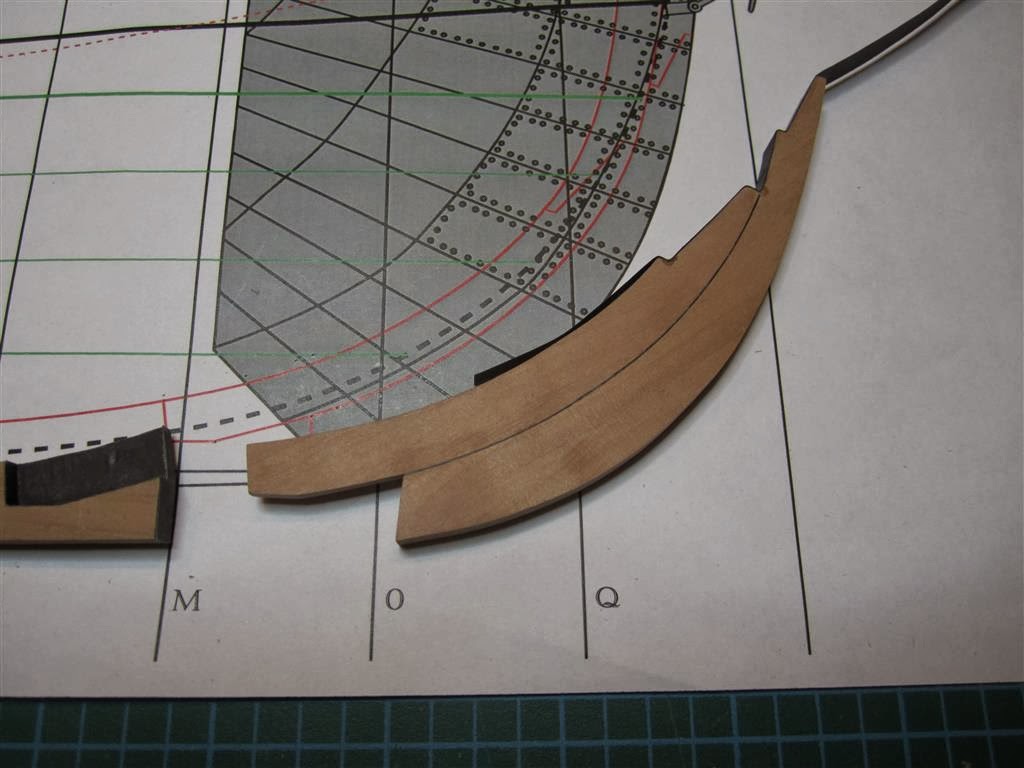

Lang’s 1845 design called for a triangular piece of wood to be

bolted to the original sternpost, creating a vertical face for the propeller

aperture. The new rudderpost and the angled fitting were both tenoned into the

keel extension, as indicated by the presence of horizontal bolts on a

contemporarymodel of the design. The entire structure was then bolted to a massive u-shaped

“staple knee”, made from 3.5 inch thick iron, which was the same length as the propeller

opening.

Lang next turned to the problem of protecting the new

rudderpost and propeller aperture from ice damage. He settled on a well system

which could be used to ship and unship the propeller, similar to a design

patented by Joseph Taylor in 1838 (Bourne 1855:32). However, Lang’s system

included a new innovation; when the propeller was unshipped, the well would be filled

with a series of stacking wooden and steel chocks. The chocks were shaped to

match the dimensions of the new rudderpost and deadwood and would completely

fill the well, thus reinforcing the rudderpost against forces exerted by the

ice.

Taylor’s patent described that the propeller could be

shipped via “vertical grooves cut in the true and false stern posts … in which

frame the propeller is placed” (Bourne 1855:32). However, the use of reinforcing

chocks required that this system be modified. Lang replaced the grooves in the

stern and false stern with robust gunmetal rails which themselves had a vertical

slot running much of their length. The protruding rails were necessary to

secure the chocks in the propeller well and needed to be very strong to endure

the pressures of pack ice (I’ll present more on the configuration of this rail

system and the propeller in a subsequent post).

While we may

never know how Lang’s chock system faired after two years in the grinding pack

off King William Island, we can surmise that it must have worked relatively

well because the Terror survived its first winter at Beechey Island in sailing

condition. Further, we know that the same chock system was installed on the

Intrepid and Pioneer (Anonymous 1850:8), steam tenders used in the Franklin

search effort, and that both ships survived multiple winters in sea ice before

being abandoned in relatively seaworthy condition.

Scantlings for Terror’s Sternpost and

Rudderpost

Sternpost

Sided:

At Head = 13 and ½

inches

At Heel = 10 and ¾

inches

Moulded depth = 17 and ½ inches

Rudderpost

Sided:

At Head = 13 and ½ inches

At Heel = 10 and ¾

inches

Moulded depth = 13 and ½ inches

References:

Anonymous

1850 Naval Intelligence — The Arctic Expedition. The

Times. Monday , 6th

May, pg 8.

Bourne, John

1855 A

Treatise on the Screw Propeller with Various Suggestions for Improvement.

Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, London.

.JPG)

.JPG)